Our Brother Is Our Life - A Sermon for the Sunday after Theophany (2023)

Our brother is our life. We’ve all heard this saying before. But have we really grasped it yet? Have we actually started to live it ourselves? Does it bear any relation to how we experience each day of our monastic life? Even in the monastery—or we might say, especially in the monastery—the force of this saying can be lost on us. Instead, we see our brethren as obstacles to be overcome, as burdens to be endured, as competitors to be defeated, or nuisances to be ignored.

How can this be? We enter the monastery as broken, atomized individuals, full of our own peculiar neuroses, our own personal traumas, our own insecurities and idiosyncrasies. We come from a shipwreck of a society, gasping for air, flailing about for any plank or life-raft that will float us to safety. In the same century that we learned how to split the atom and release its awful, destructive potential, we also learned how to unleash the destructive power of the human ego by splitting it apart from all the structures and authorities that used to shape it, direct it, and give it meaning. Everything in our culture teaches us that instead, we’ll find happiness and fulfillment by liberating our ego from all higher authority and giving free rein to our desires. But if we’re honest with ourselves, we’ve never been more miserable. With each passing year, we see the rates of anxiety, despair, depression, and suicide continue to rise, especially in the youngest generations.

Surely we know all this well enough, otherwise none of us would be here seeking a way out of it. Even if we can’t clearly articulate it, we can sense that we’ve been trapped in the prison of our own egos, and that this imprisonment is the real source of all our psychological and spiritual problems—anxiety, depression, malice, envy, hatred, pride, vanity, anger, laziness, sadness, sensuality, despair, boredom, distraction. Even an honest psychologist could tell you that, for a fee. But outside the Church, the only thing we’re offered to deal with these problems is self-help, self-improvement, self-actualization, as though the self could ever possibly help us break free of our selves.

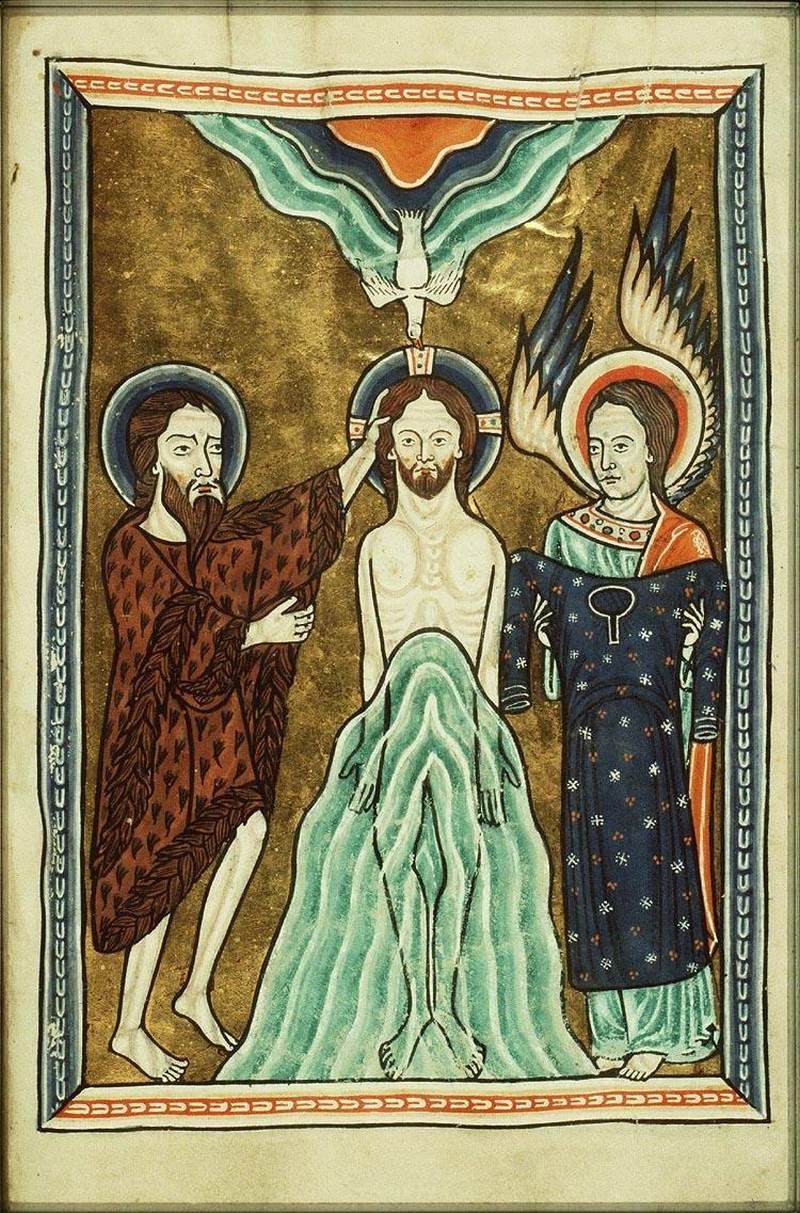

In Baptism, we’re offered a real path to freedom. But it’s not simply magic; we have to cooperate rightly with the grace we’re given in order make it active. We’re called to leave behind the barren, sterile, deathly life of the ego, and enter into the glorious unity of faith, into the one and only body of the one and only Christ.

Baptism is the fulfillment of the Old Testament circumcision; just like circumcision, it marks our entry into a community, into the people of God, the spiritual Israel. In the early Church it was said, “One Christian is no Christian.” So we see that we’re never saved alone, on our own strength or merits; we’re saved together in community, together as one body, the Body of Christ. As St. Paul writes to the Ephesians, There is one body, and one Spirit, even as ye are called in one hope of your calling; one Lord, one faith, one baptism, on God and Father of all, who is above all, and through all, and in you all (Eph. 4:4-6).

But our stubborn ego is in constant tension with this ideal of unity that St. Paul expresses so beautifully. For us monks especially, we are forced to confront this tension day in and day out as we try to live the life of the Gospel together in community.

The ego lives by the famous dictum of Sartre, L’enfers c’est les autres—hell is other people. And brothers, I love you all dearly, but I can say that I never understood the full force of that saying until living in the monastery. When our fallen ego is forced to confront other people all the time, then we see all the hellish darkness that’s locked inside us. Sure, sometimes other people’s behavior can annoy or irritate us. We can at least justify that to ourselves. But some mornings, you wake up on the wrong side of the bed, and the mere presence, the mere existence of other people is a torment. Maybe it’s just me, but I don’t think so.

Hell is other people. Our brother is our life. These are our two choices, the way of death and the way of life, the ladder to heaven or the road to hell.

We know what we ought to choose, but how do we do it? How do we actually break free of the prison of the self? The scientists say that fusing two atoms together takes a great deal more energy that it does to split them. But this fusion reaction can also generate a tremendous amount of energy. Stars and galaxies are formed from it. So we have to force ourselves to collide with our brother, so to speak. We have to force ourselves to encounter him, to shatter our own fragile ego against him, so we can make room for him in our heart. We have to make an inward effort to set off the fusion reaction that will bind us together in God’s love and generate new spiritual life.

This kind of inner exertion is true and saving asceticism. This is the fulfilment of our baptism, the spiritual circumcision, the cutting off of our own fruitless and harmful self-will by accommodating the will of our brother. When we’re used to doing our own will all the time, exerting ourselves in this way creates pain in our heart. But this is good. This brings compunction, that inner wound that pierces our callous heart and finally allows the love of God to make its way in.

Just start small, it doesn’t take much. Even a small act of kindness to a brother, even just a kind word or a smile, can bring a great amount of grace—both to you and to him. It may be that your brother is feeling as though hell really is other people, and your small act of kindness will pull him back from the brink of misery and despair. You might show him that his brother is his life. He who is faithful in little is faithful also in much. We won’t be able to make big sacrifices for our neighbor if we don’t start with little ones. St. Sophrony says that he who loves more humbles himself the more. The more we grow in God’s love, the easier it is to yield to our brother.

Our brother is our life. St. Anthony also tells us that our salvation lies with our brother. Our monastery typicon tells us that we’re not supposed to live like a random collection of bachelors, just existing alongside one another without ever really encountering one another. But isn’t that still too often the case? Is it not a constant temptation to retreat into the comfortable confines of our ego? We have to examine ourselves and see whether we’ve grown spiritually stagnant, whether we just settle for going through the motions of monastic life without ever striving for or experiencing the brotherly love and unity to which we’re called.

We have to apply ourselves if we want to activate the grace of our baptism. But it’s important to remember that unity does not mean identity or equality. Our goal is not to become interchangeable cogs in a well-oiled machine. We are each members of one body. Our capacities, strengths, and weaknesses are all different, but we all have our part to play, we all have something vital and necessary to contribute to the life of our brotherhood. As St. Paul says in today’s epistle reading, unto every one of us is given grace according to the measure of the gift of Christ (Eph. 4:7). Whatever gifts Christ has given us, whether they are our natural gifts given at birth or spiritual graces He has given us in the course of our Christian struggle, all of them are given to us so that we can labor for the good and salvation of our neighbor. Our gifts are meant for each other.

We might be tempted to think that it’s immodest to exert ourselves, to put ourselves forward, to make full use of our gifts. But this is false humility, this is burying our talent in the ground like the wicked and slothful servant in the parable (cf. Mt. 25:26). On the other hand, we’re asked to do more than just show off our talents. Showing off means to make use of them exclusively according to our own judgment and inclination, in order to impress others and seek praise. This is mere vainglory, pure egoism. This profits neither us nor our neighbor. No, we have to multiply our talents by putting them to use in the service of our brethren. This is how we really die to ourselves, and break out of the prison of the ego. It means we have to put forth a wholehearted effort to do the very best we can in our obedience, but then be detached enough from the fruit of our labor that our brothers can criticize it, change it, or reject it without us losing our peace. This is death to the ego, but for the spirit this is life.

Our brother is our life. Our encounter with him is the only way we can grow in love. Of course, it’s not always easy; of course, there will be conflict between us, disputes, disagreements. But St. Paul reminds us, Be angry and sin not; let not the sun go down upon your wrath: neither give place to the devil (Eph. 4:26-27). If we quarrel at times, if our egos are bruised when we collide with one another, that’s okay, that’s to be expected. Just let it be brief and don’t let the bond of charity be broken.

Don’t retreat from your brother and let your wounds fester, don’t let resentment build up in your heart. That’s why St. Paul also tells us to speak the truth in love to one another (cf. Eph. 4:15). If your brother offends you, or if he regularly does something that disturbs you, it’s okay to say something to him. Christ says to rebuke the brother that offends us (Lk. 17:3). But he doesn’t mean—lash out at him, tell him off, get even with him, put him in his place, cuss him out and walk away. That’s what happens when we let resentment build up in us. That’s what happens when the sun sets on our wrath, over and over again. We have to speak the truth in love. Our desire should always be to gain our brother, and for our brother to gain us. For we gain ourselves in gaining our brother. No matter how frustrating he may be sometimes, never stop trying to love your brother. Our brother is our life. You won’t be able to live with God if you can’t live with him. And just think—we’re meant to live with each other for ever. But if we still live here as though hell is other people, then even in Paradise we’ll find torment.

When we finally learn that our brother is no obstacle of our salvation, but is rather the very essence of our salvation, then we will rejoice at his successes, we will desire his good and strive for his wellbeing; because we know that we need his gifts to help us, to help make the body whole. We will rejoice, because we know that the same Lord who loves us, and blesses us, and died for us, also loves him and died for him. So brothers, let us labor wholeheartedly to make this brotherly unity a living reality in our daily lives, until, as St. Paul says, we all come in the unity of faith, and of the knowledge of the Son of God, unto a perfect man, unto the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ (Eph. 4:13). Amen.

beautiful!

Leave a comment