Beneath the Banner of the Cross – A Homily for the Third Sunday of Great Lent (2021)

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

In ancient times, armies would carry a banner into battle. It was needed to identify the warring parties. Each side’s banner symbolized who they were, and what they fought for. If an army’s ranks were broken, the soldiers could look to their banner, and rally around their comrades to launch a fresh assault against the enemy. The mere sight of the banner of a mighty, unconquerable army could strike fear into the hearts of its foes. And when an army was victorious, its banner was carried at the head of the victory procession, inspiring joy and exultation among the triumphant soldiers, and those back home whom they had fought to protect.

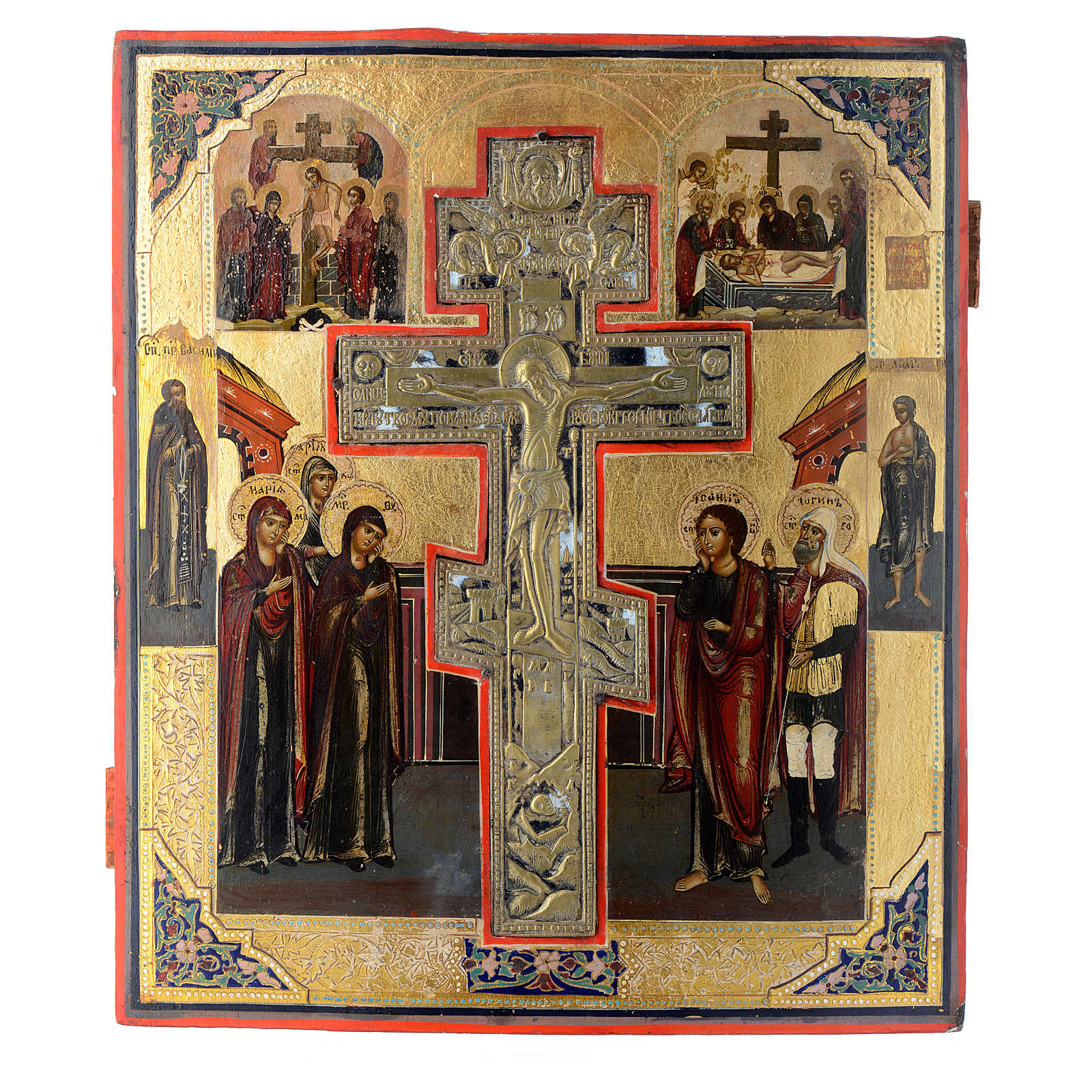

Today, we reach the midpoint of the Great Fast, and it is with the same exultation that we greet the precious Cross of the Lord. Today, in the midst of the struggle, in the heat of the battle, the Church unfurls her banner for us, and like good soldiers of Christ, our hearts are renewed. Though we are wearied from three weeks of fasting, we find fresh vigor to undertake the remaining toils with prowess and zeal—confident in the spoils of victory and the glories of triumph that await us on Pascha night if we continue to wage a good warfare. Though our hands grow slack, and our backs grow slump, though our knees are weak from fasting, and our flesh is changed for want of oil (cf. Ps. 108:24), the Cross of Christ is an inexhaustible well of gracious strength. If we stay ourselves upon it, we will always find it to be steadfast and unshakeable. And just as Israel prevailed over Amalek only when Moses’ arms were stretched out in the form the Cross, so too the sight of the Cross displayed in our midst brings us courage, and spiritual reinforcements. Our spiritual enemies hate the sight or even the mention of the Cross. In their malice, they try to negate its force by stirring up temptations for us, both inward and outward. Let us not be deceived; their malice only cloaks their impotence. Armed with the might of the Cross of Christ, let us rather despise them and press on the attack, saying, The Lord is my light and my saviour, whom then shall I fear? The Lord is the defender of my life, of whom then shall I be afraid? Thou hast girded me with strength for the battle; thou hast enlarged my steps under me and my feet slack not. I will pursue mine enemies and overtake them, I will not turn back until they fail; I will smite them and they shall not be able to stand, they will fall beneath my feet (Ps. 26:1, Ps. 17:37-40).

The Lord calls us to such confidence in today’s Gospel. He warns us not to be ashamed of Him and His gospel in this adulterous and sinful generation. He spoke this to the whole multitude of people just after He had revealed privately to the Apostles His impending suffering and death. Peter rebuked Him, thinking instead of the glory of an earthly kingdom and a political messiah. For his misguided mercy, the Rock of the Church was called Satan, and the one who just moments before had confessed Christ’s true identity by the special inspiration of the Father, now learns in no uncertain terms that there is no Christ without the Crucifixion; there is no Kingdom without the Passion.

We live on the other side of 2,000 years of Christian history. During that time, the Christian faith conquered the greatest Empire on the face of the earth; nations and civilizations have embraced, defended, and fought for the Cross, placing it at the heart of their cultural identity; men tried to realize as much as possible the ideal of the Kingdom of God, a Christian society, here on earth. These historical triumphs of the faith can make it easy for us to lose sight of the inherent scandal of the Cross; of how, from a human point of view, the faith of Christ was a most unlikely contender to be an epoch-making world faith.

To the respectable society of Christ’s time and of the early Church, Christianity often appeared as little more than a hysterical and pernicious superstition. How could anyone believe that an undistinguished Jew, the lowly son of a carpenter, rejected by his own countrymen, and put to death by a Roman governor, was almighty God? Not content with their ridiculous beliefs, the adherents of this new faith were also disruptive in public life. They refused to participate in all of the pagan rituals embedded in Roman society. These were often mere formalities—many people didn’t take them seriously, or have a sincere faith in the pagan deities. It was simply what decent people did to be good, normal members of society. But these Christians stubbornly had to be different, insisting that the usual customs of respectable society were really sacrilege and impiety. Even more embarrassing, Christians would associate with their social inferiors on terms of equality, ignoring the social boundaries that separated slave and free.

But what was shame in the eyes of the wise and prudent of this world was glory to those who believed. Like St. Paul, they were not ashamed of the gospel of Christ, for it is the power of God unto salvation to every one that believeth (Rm. 1:16). They considered not the scorn of men or the contempt of the uncomprehending world, but rather heeded the dreadful words of Christ, Whosoever shall be ashamed of me and of my words in this adulterous and sinful generation, of him also shall the Son of man be ashamed, when he cometh in the glory of his Father with the holy angels (Mk. 8:38).

As false prophets and false gospels proliferate in our own day, we should also take the Lord’s word deeply to heart. There are Christians of all stripes now who would try to reconcile the Cross of Christ with world. Having turned their gaze from the Cross, they identify the Kingdom of God with their own political inclinations, and immerse themselves with apocalyptic fervor in earthly cares. Some look with messianic expectation to fallen, sinful men, and hope to bring about a godly Christian society through the application of political power and worldly influence; others reject the gospel of Christ altogether, eschewing “salvation theology” as an outmoded tool of oppression and embracing “liberation theology” in pursuit of an earthly reign of perfect justice and equity. All such hopes are false and vain—they offer us a Christianity without the scandal of the Cross. For the Cross is always inimical to the false pieties that men devise for themselves in order to confirm their own prejudices or to display their supposed virtues to one another. If we are true Christians, then the Cross is our banner; we rally to it alone, and we say with the Apostle, God forbid that I should glory save in the Cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world is crucified to me, and I to the world (Gal. 6:14).

If we love the Lord Jesus and His Cross, if we despise the shame of being a true follower of Christ, if we are ready to do battle against the devil and his angels, and the passions of our fallen nature, we should know how to wage war skillfully, lest we end up simply beating the air. Here again, we find the Cross becomes our weapon. If we wield it with knowledge, we will behead the spiritual Goliath; like a wooden battering ram, the Cross will shatter the brazen gates of the enemy’s strongholds, and we will put him to flight. Only through the Cross will we achieve anything of value in the spiritual and earthly realms, because only through Cross does the grace of God operate. The first Christians understood this; they possessed this grace that flows from the Cross, and hence they had boldness and daring in their confession of Christ. Through the Cross, they lived in Christ. And this is how they convinced an unbelieving and hostile world, steadily spreading the Gospel and increasing the Church despite various waves of persecution. In the face of their suffering, the pagans could see that the Christians were genuine, and genuinely different. They could sense the grace of God at work within them.

We too must bear the same mark of authenticity if we are to bear witness to an indifferent and often antagonistic world. This mark, this seal, is the Cross. We earn it by carrying the yoke of the Cross. This is what Jesus speaks of when He says, Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy-laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn of me, for I am meek and lowly in heart, and ye shall find rest unto your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light (Mt. 11:28-30). We labor and lade ourselves with burdens when we serve our own passions. They build up over time and become an intolerable weight for us, piling on sin after sin, until we cry out like David, Mine iniquities are gone over my head, as a heavy burden they press heavily upon me! (Ps. 37:5). We indulge our passions, thinking they will give us life; and so we come to think that life is only this service of the passions and lusts of our nature. But Christ assures us that whosoever will save his life shall lose it, but whosoever shall lose his life for my sake and the gospel’s, the same shall save it (Mk. 8:35). In this season of Lent, the Church calls us to divest ourselves of this yoke of the passions, to lose our own life, and to take up the easy yoke of Christ’s Cross.

How can an instrument of torture be easy? How can fasting, long prayers and standing be light? When we also take up the inner Cross that Christ speaks of—meekness and lowliness of heart, the cutting off of our own will, humbling ourselves before one another, preferring one another in honor, bearing one another’s burdens, in short, loving our neighbor as ourselves. If we harrow our hearts with the Cross of fasting and plant these seeds in the furrows, we will see the fruit of the Spirit begin to spring forth—love, joy, peace, and the rest (cf. Gal. 5:22-23). Nourished on these fruits, we will doubtless find Christ’s promised rest. Thus we find that it is not the ascetic discipline of the Fast that is heavy, but our own self-will and pride, which constantly cause us to oppose ourselves, and to exert ourselves in vain. But when we take up the Cross as a yoke, we can run the course of the Fast easily and swiftly, lightened of the physical burden of excess foods, and of the spiritual burden of our passions.

As we embark on the remainder of the Fast, let us take courage in the Cross that is now set before us. The hymns of the Triodion have prepared us for this, and they will continue to exhort us as the week draws on. If we’ve been struggling and keeping the Fast well, let us renew our initial resolve and see our good labor through to the end. If we have lost our first rigor, and grown faint from the hardships of the Fast, let us take this opportunity to make a new beginning, to redouble our efforts, and to fight the good fight. Half of the Fast lies before us; let us walk while we have the light of day. The Fast is a time of penitence, yes, but also of deep and sober joy, joy that comes from the lightness and newness of life we feel when we have shed the burdens of our sins. The Church constantly calls us to undertake the labors of the Fast with eagerness, just as the Lord Jesus walked in front of His disciples on the road to Jerusalem, thirsting to undergo His suffering for the salvation of the world. So let us follow Him to His Passion with the same zeal, that we might come in due time to the glorious joy of His Resurrection. Amen.

Leave a comment