Sermon for the 23rd Sunday after Pentecost

The Scriptures, and especially the Gospels, are full of stories like those which we have just heard: stories of the miraculous power and the mercy and compassion of our God. As Christ said to the disciples of the Forerunner: “Go and shew John again those things which ye do hear and see: The blind receive their sight, and the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, and the deaf hear, the dead are raised up, and the poor have the gospel preached to them.” The first three Gospel books are dedicated almost entirely to telling of the healing miracles which the Saviour performed for the countless multitudes which came to Him.

Yet behind these stories there is very often another story, one which is quite different. They are almost always the stories of people who were left to suffer for years or even decades on end, both righteous and sinners alike, without any sign that the Lord heard their prayers or cared about their pain. The woman with an issue of blood in today’s Gospel had suffered for twelve years, and though she spent everything she had in the world and was left with nothing, she had only grown worse. One man laid by the Pool of Bethesda for thirty-eight years, forced time and time again to watch others be healed by the power of God, while he himself was left alone with no man to help him. The poor man Lazarus laid all his life starving outside the rich man’s house, seeing him fare sumptuously every day, while Lazarus himself had no one even to drive away the dogs which came to lick his sores. Zacharias and Elizabeth, Joachim and Anna, though righteous beyond any in their generation, spent all their lives under the curse of barrenness, perceived by their world as the ultimate sign of God’s judgment and displeasure. And finally, in the Gospel of John there is written what is, on the surface, perhaps the most incomprehensible statement in all of Scripture: “Now Jesus loved Martha, and her sister, and Lazarus. When he had heard therefore that he was sick, he abode two days still in the same place where he was.”

And so often the same is true with us. We pray, and we are not healed. We beg the Lord to spare our loved ones, only to watch them die. We come to the Holy Church, we partake of the Holy Mysteries and confess before the Lord our sins, yet our passions do not go away. We come to the monastery to repent, and though we have lived the monastic life for year after year, sometimes our sinfulness only seems to have grown worse.

The most common–and the most powerful–argument raised by unbelievers is this: why, if He exists, would an all-good and all-powerful God allow such evil, pain and suffering in the world? If we truly and honestly face the realities of the world around us, we cannot but be cut to the heart by this question. More than at any other time in the history of the world, we look around us and see such hatred, depravity, suffering, brutality, and meaninglessness that to really see and understand it all would be too much for almost any of us to bear. And though the Christian philosophers and apologists may raise many clever arguments and make many good points, the truth is that no argument they could possibly make can mean anything in the face of the evil, suffering and death that engulfs the world in which we live.

And yet, despite all of this, we believe with all our hearts in a God of unfathomable love, mercy and compassion.

Why? Is it because, as in the case of today’s Gospel, these stories all have a happy ending? All too often the stories do not. “Strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life.” In a world with men and women of free will, there can be no guarantees of a happy ending. The suffering and pain that lead some to repentance all too often has lead others only to bitterness, despair and death.

And again, despite all of this, we believe with all our hearts in a God of unfathomable love, mercy and compassion.

There is no argument that could convince anyone of this. There is no rational explanation, no theodicy, no intellectual justification that explains neatly and tidily why God has created and allowed such a world as this. There is–and can be–only one answer.

The answer, in the words of one contemporary Orthodox theologian, is this: “For us, Love is the figure of a dead Jew, a corpse, hanging on the tree of the Cross outside the holy city of Jerusalem, betrayed by His own people, killed by the Gentiles in the most vile death that a human being can die.”

It is not primarily in the miracles and the healings of Christ that we see His love; it is in His death and in His sufferings. He did not come into this world to take away our pain and sorrow, or even to take away from us our death, but rather to enter into these things Himself, though He deserved them far less than anyone, and to transfigure them by His deifying presence, to bear the very worst of our ugliness and sinfulness, to take on Himself the most extreme sorrow, the worst pain and the most vile death–all the consequences of our fall–and to turn them into the very means of our salvation and union with Him. He came and followed us even to the very depths of hades, so that no matter what darkness may cover us, no matter what evil we may see around us or inside of us, no matter what emptiness may fill our hearts, we can truly say with our whole soul and with our whole heart: “God is with us!”

We do not believe in the love and power of God in spite of evil, sin and death. We do not justify the fact that He has allowed them, but rather we believe because He Himself accepted all these things Himself. The Fathers teach us that God could have chosen another way to save us–but He chose this way, because it most perfectly showed to us His love.

And He has given us this as a way to show our love for Him: to trust, without any rational proof or logical guarantee, that if He allows us to suffer, if He allows us to grow sick, if He even allows us or those around us to die, it is only out of love for us and for the sake of our salvation. To believe with all our hearts that “This sickness is not unto death, but for the glory of God, that the Son of God might be glorified thereby.” As another contemporary author has written: “This is a great honor–to hear God’s silence in your life and to answer it with thankfulness!”

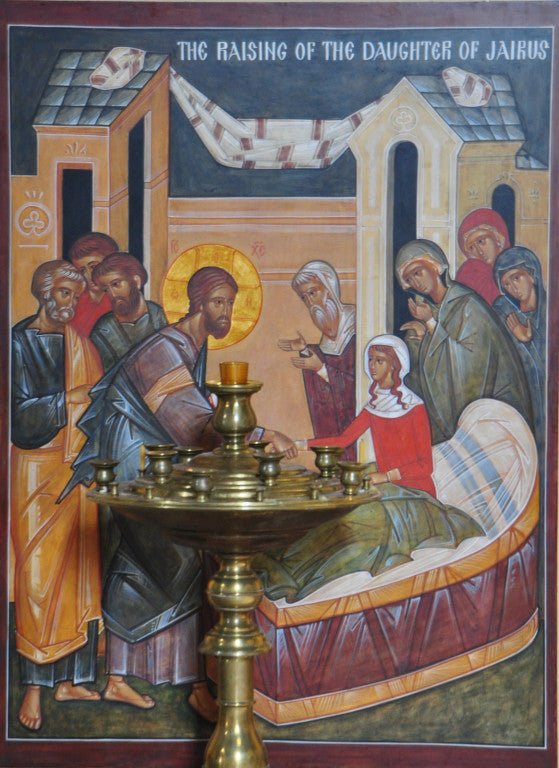

And let us not forget that many of the happy endings to these stories did not come at all during the course of this earthly life. Jairus’ daughter was dead. Lazarus the beggar and Lazarus the friend of Christ were dead. The thief’s one redeeming moment did not come until the last moment of his life; it was only as he hung dying on a tree, with no hope left to him on this earth, that he made his confession of faith and had the doors of paradise opened to him.

That is why we do hear so many stories with happy endings in the Gospels–so that we would know and be sure that even if we ourselves never see or experience anything like it in this broken world, “Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love him.” Amen.

Leave a comment